The Yale Childcare Consultative Committee (CCC) has launched an op-ed in the Yale Daily News, titled: “Yale Needs Pandemic Plan for Working Parents. ” The op-ed was published by the chair of WFF Naomi Rogers (professor of history), the co-chair of WWN Stacey Bonet (senior administrative assistant at the School of Public Health), and WFF Steering & Council member and CCC lead researcher Rene Almeling (associate professor of sociology).

“With COVID-19 cases on the rise in Connecticut, and daycares and schools closing down, the effects of the pandemic are growing more severe every day. The time has come for Yale to adopt comprehensive and, importantly, structural policies to address the enormous pressure on caregivers during this time.”

The full briefing, which includes interviews with Yale faculty and staff, research and data on COVID’s gendered impacts in higher education, and a call to action for comphrensive childcare policies at Yale, can be found here and below.

***

New Childcare Committee Calls on Yale to Offer Comprehensive Plan for Working Parents During the Pandemic

The Yale Childcare Consultative Committee (YCCC) is a coalition including leaders from the Women Faculty Forum, FAS Senate, Committee on the Status of Women in Medicine, Working Women’s Network, Yale postdoctoral associations, and UNITE HERE Local 34. We applaud Yale for the steps taken thus far to support faculty and staff experiencing tremendous strain as they attempt to balance working and parenting during this time. Yet the new policies are proving too limited, especially as the pandemic worsens. Recent peer-reviewed research documents the dire situation facing working parents and mothers in particular. Interviews with faculty and staff at Yale reveal similar challenges in our own community. We call on the Yale administration to develop a comprehensive plan to support caregivers for the remainder of the pandemic.

The Data

COVID-19 has laid bare and exacerbated gender inequities in the workplace and at home. Women in the United States have long worked a “double shift” – even as they join the labor market in ever-larger numbers, they still continue to take on the lion’s share of household tasks, childrearing, and elder care (Bianchi et al. 2012; Hochschild 1989; Iversen and Rosenbluth 2010). These inequities persist in the additional domestic labor brought on by the pandemic: while men now contribute more time to care-work than before, women (especially in low-income households) continue to shoulder the larger burden (Oxfam 2020). Yale researchers determined that American mothers working from home in April and May 2020 spent substantially more time on housework than fathers (Lyttelton 2020).

Already stretched before the pandemic, working mothers now face the impossible with schools and daycares reducing their hours or closing outright. In response, many women are cutting back to part-time or leaving the workforce altogether (Collins 2020). The most comprehensive surveys to date find that 1 in 4 women are considering downshifting or quitting due to COVID (Women in the Workplace 2020). Indeed, the federal government’s Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that in September 2020, 865,000 women voluntarily dropped out of the workforce – 4 times the number of men who did.

When it comes to faculty, women with young children are experiencing dramatically reduced time for research. Across academic disciplines, multiple studies have documented that, since the pandemic began, women are producing fewer research papers than their male counterparts, and the pattern is especially striking for solo-authored articles (Cui et al. 2020; Kim & Patterson 2020; Myers 2020; Patino et al. 2020). These are early warnings about the gendered effects of COVID on academic productivity, which could prove devastating for an entire generation’s prospects of promotion and tenure.

The bottom line: We are only beginning to see the effects of this public health crisis on working parents. Without bold action by employers, progress on gender equity could be decimated for decades to come.

“A Day in the Life” of Working Parents at Yale During the Pandemic

To learn more about how these dynamics are playing out on our own campus, Yale sociologist Rene Almeling spoke to staff and faculty with young children about their experiences over the past eight months. When asked to sum up the situation, many of them used the same drowning metaphor: “I am barely keeping my head above water.” Even as they expressed gratitude for their relative privilege as Yale employees, they described uncertainty plaguing every aspect of their daily efforts to juggle work tasks and childcare. When would schools re-open? Would a case of the sniffles lead to lost days of daycare? Could they find a sitter they trusted? Would the weather be nice enough for an older relative to watch the child outside for a few hours? Here are three of their stories in more depth.

Marijeta Bozovic is an assistant professor of Slavic Languages and Literatures at Yale. Entering her seventh year at the university, she felt “momentum,” working through edits for her second book and serving as an editor for several professional journals. Then the pandemic hit. She and her husband, Tim Newhouse, an organic chemistry professor who just received tenure at Yale, endured five long months without any childcare or familial support. Their days were completely consumed with caring for their 3-year-old and infant. “Everything ground to a halt. My ability to work was just devastated. There are not strong enough words to describe it.” For now, their children are in school and daycare for part of the day, allowing them to meet basic teaching and service obligations, but the lost hours and months remain an issue. Marijeta noted it was particularly hard to lose an entire summer before tenure, as summer is when many faculty in the humanities focus on writing. She concluded by discussing her worries about the long-term effects of the pandemic on her generation of women in academia: even those who achieve tenure will do so later, further delaying leadership positions and affecting the whole system for years to come.

Marijeta Bozovic is an assistant professor of Slavic Languages and Literatures at Yale. Entering her seventh year at the university, she felt “momentum,” working through edits for her second book and serving as an editor for several professional journals. Then the pandemic hit. She and her husband, Tim Newhouse, an organic chemistry professor who just received tenure at Yale, endured five long months without any childcare or familial support. Their days were completely consumed with caring for their 3-year-old and infant. “Everything ground to a halt. My ability to work was just devastated. There are not strong enough words to describe it.” For now, their children are in school and daycare for part of the day, allowing them to meet basic teaching and service obligations, but the lost hours and months remain an issue. Marijeta noted it was particularly hard to lose an entire summer before tenure, as summer is when many faculty in the humanities focus on writing. She concluded by discussing her worries about the long-term effects of the pandemic on her generation of women in academia: even those who achieve tenure will do so later, further delaying leadership positions and affecting the whole system for years to come.

Katie Darr is Director of Development at the Yale School of Music, and her husband has a remote postdoctoral fellowship at Princeton. When asked to describe a typical day with their 6-year-old and twin 4-year-olds, she said, “There is no typical day or typical week, and that’s what makes it so difficult. It’s impossible to plan ahead, and every day we’re sitting down to map out who has which meetings and how can we make sure someone is keeping an eye on the kids.” They cobbled together various sources of childcare, including 10 hours a week from a graduate student living with them. In the summer, they podded up with another family to share a babysitter. For the first part of the fall, they counted themselves lucky that Elm City Montessori offered in-person pre-school for the twins, but it was only open two days a week from 9:00 am to 12:30 pm. Each drop-off and pick-up took 25 minutes, cutting into precious work time. However, at the end of October, the week after we spoke, the school shut down completely because of rising COVID cases in Connecticut. Katie is grateful to have a supportive boss who understands that now she sometimes has to rush to get the basics done because “you never know when the day is going to get completely derailed.”

Katie Darr is Director of Development at the Yale School of Music, and her husband has a remote postdoctoral fellowship at Princeton. When asked to describe a typical day with their 6-year-old and twin 4-year-olds, she said, “There is no typical day or typical week, and that’s what makes it so difficult. It’s impossible to plan ahead, and every day we’re sitting down to map out who has which meetings and how can we make sure someone is keeping an eye on the kids.” They cobbled together various sources of childcare, including 10 hours a week from a graduate student living with them. In the summer, they podded up with another family to share a babysitter. For the first part of the fall, they counted themselves lucky that Elm City Montessori offered in-person pre-school for the twins, but it was only open two days a week from 9:00 am to 12:30 pm. Each drop-off and pick-up took 25 minutes, cutting into precious work time. However, at the end of October, the week after we spoke, the school shut down completely because of rising COVID cases in Connecticut. Katie is grateful to have a supportive boss who understands that now she sometimes has to rush to get the basics done because “you never know when the day is going to get completely derailed.”

Jeni Atchley is a registrar at the Yale School of Medicine, and her husband works in IT support at the university. They are both working remotely while trying to make sure their 3-year-old is safely occupied. Prior to COVID, their daughter was in pre-school 2 days a week, and both their mothers would take turns watching her the other 3 days. “Now we are just home all the time. My husband is slightly higher-risk, so the only help we get is when the weather is nice and one of our moms can be masked with her in the backyard.” Jeni and her husband constantly pivot between meetings that pop up, tasks that need to get done, supervising their daughter, and resorting to television as needed. They wake up early to squeeze work in and stay up late to finish it. “I do not want a pity party. We are making it work, but it is a real struggle right now. I just wish there were a safe way for her to be taken care of outside our home.” She is especially worried about winter; the cold weather will make it even more difficult for them to get the help they need.

Jeni Atchley is a registrar at the Yale School of Medicine, and her husband works in IT support at the university. They are both working remotely while trying to make sure their 3-year-old is safely occupied. Prior to COVID, their daughter was in pre-school 2 days a week, and both their mothers would take turns watching her the other 3 days. “Now we are just home all the time. My husband is slightly higher-risk, so the only help we get is when the weather is nice and one of our moms can be masked with her in the backyard.” Jeni and her husband constantly pivot between meetings that pop up, tasks that need to get done, supervising their daughter, and resorting to television as needed. They wake up early to squeeze work in and stay up late to finish it. “I do not want a pity party. We are making it work, but it is a real struggle right now. I just wish there were a safe way for her to be taken care of outside our home.” She is especially worried about winter; the cold weather will make it even more difficult for them to get the help they need.

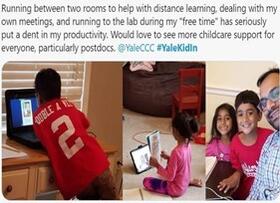

The difficulties of constantly juggling work and family during the pandemic are also evident in pictures posted by faculty and staff during the #YaleKidIn, a virtual sit-in on social media during the week of October 26th:

|

|

|

Yale Childcare Consultative Committee’s Call to Action

With COVID cases on the rise in Connecticut, and daycares and schools closing down, the effects of the pandemic are growing more severe every day. Yale has rightly called for flexibility by department chairs and managers whose employees are shouldering heavy caregiving responsibilities, but the result has been wide variation in accommodations across campus. Some department chairs have reduced teaching and service expectations for faculty. Others have done nothing. Some managers are doing everything they can to ease the burden on staff, such as taking into account the “extra” work spurred by the pandemic and allowing people to organize work hours around remote schooling and childcare. Others have done nothing.

The consequences of COVID, both gendered and otherwise, are too significant to be left to the discretion of individual chairs and managers. And untenured faculty and staff should not be required to ask for special treatment from deans and supervisors. We are deeply appreciative of the collaborative efforts made by Provost Scott Strobel and FAS Dean Tamar Gendler, and we offer the following suggestions as additional steps that Yale should take.

- 2020 has not been business as usual, and Yale must do more to address faculty and staff workloads during this unprecedented global health crisis. Yale should offer detailed, clear guidance to department chairs and managers about what it means to be “flexible” about when and where work happens. For faculty, it could include reducing teaching loads and class sizes whenever possible, as well as postponing non-essential service until after the pandemic. For staff, it could include allowing flexible hours, a compressed work week, and focusing on the completion of tasks rather than how long they take.

- For those who simply cannot work because either they or their children are quarantining or sick with COVID, Yale should join peer institutions in creating a special category of “COVID days” that provide paid time off for COVID-induced sickness and/or caregiving. At present, employees have sick leave and paid time off, but many have already burned through those days due to COVID. This is a rapidly-spreading disease that can cause illness for weeks and months; offering additional paid time off will reduce the pressure employees feel to show up for work or send their children to daycare when they might be ill. We advocate that Yale offer up to 90 “COVID days” through June 2021.

- There was already a childcare crisis at Yale before the pandemic and offering a few spaces at Bodel and Bright Horizons is not sufficient, given that many people cannot afford the spots or commute there easily. The administration is exploring the possibility of additional childcare on campus, and we strongly encourage Yale to prioritize the creation of affordable, high-quality childcare on central campus and other convenient locations to serve Yale faculty, staff, postdoctoral scholars, and graduate students both now and in the future. First steps might include issuing an RFP for local providers to establish new centers and designating space for childcare in new building projects.

- Yale’s Crisis Care Assist emergency back-up program has been deeply appreciated by working parents across campus. The Provost recently announced an increase in the number of days from 20 to 25, but faculty and staff need to be able to plan ahead. We ask that Yale expand the Crisis Care Assist program to a total of 50 days through June 2021. If this benefit cannot be secured through Bright Horizons, then Yale should consider direct cash subsidies to assist with the unexpected costs of childcare during this time.

- Faculty on the tenure track are both grateful and conflicted about the opportunity Yale has offered to extend the clock. While it technically provides more time to complete research before review, many are concerned about a concomitant rise in expectations, especially those that do not take into account women’s often-greater caregiving burdens. Moreover, it is not just parents who have found themselves without much time to do research, as the work of teaching and service has increased due to the pandemic. We urge Yale to incorporate clear guidance to tenure review committees about how to assess productivity during this pandemic year and give junior faculty the opportunity to include a “COVID statement” about interruptions to their research. Further, we advocate that all junior faculty be provided with one additional semester of paid research leave (or two course releases) prior to tenure. We also encourage Yale to recognize that work/life balance remains difficult for tenured women faculty during this time. One suggestion would be to institute a process through which anyone suffering research setbacks due to COVID-related caregiving can request research leave.

- Postdoctoral scholars are experiencing stalled professional progress and additional financial burdens due to unexpected childcare costs, especially because they are less likely to have extended support systems locally. Postdoc parents hired on limited appointments or those running short on funding are particularly vulnerable. To ease the tremendous strain, we ask that postdocs receive a stipend to help cover the costs of childcare, be offered the opportunity to extend their appointments (as junior faculty and many graduate students have), and be able to apply for additional funds to support interrupted research.

- After completely freezing M&P salaries in the spring, Yale recently announced that full-time M&P staff making less than $85,000 per year would receive a 1.5% raise. However, in line with national trends, many women M&Ps have ratcheted back to part-time due to pandemic-related childcare demands. They will miss out on this crucial increase in salary, which could further contribute to the gender wage gap. We ask that Yale expand the 1.5% salary adjustment to all M&P staff.

The time has come for Yale to adopt comprehensive and, importantly, structural policies to address work/life balance during the pandemic. We look forward to continuing our discussions with the Provost’s Office and hope these efforts provide significant relief to those attempting to balance work and family during this time.

Brief presented to President Salovey and University leadership on December 1, 2020. Researched by Rene Almeling, Annabelle Hutchinson, & Oana Capatina.

References

Amano-Patiño, N., Faraglia, E., Giannitsarou, C. and Hasna, Z. 2020. “The Unequal Effects of Covid-19 on Economists’ Research Productivity.” Cambridge-INET Working Paper WP2022.

Bianchi, S. M., Sayer, L. C., Milkie, M. A., & Robinson, J. P. 2012. Housework: Who Did, Does or Will Do It, and How Much Does It Matter? Social Forces 91(1), 55–63.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Current Employment Statistics.” September 2020.

Collins, Caitlyn, Liana Christin Landivar, Leah Ruppanner and William J. Scarborough. 2020. “COVID-19 and the Gender Gap in Work Hours.” Gender, Work & Organization.

Cui, Ruomeng, Hao Ding and Feng Zhu. 2020. “Gender Inequality in Research Productivity During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Available at SSRN 3623492.

Hochschild, A. R., & Machung, A. 1989. The second shift: working parents and the revolution at home. Viking.

Iversen, Torben and Frances McCall Rosenbluth. 2010. Women, work, and politics: The political economy of gender inequality. Yale University Press.

Kim, Eunji and Patterson, Shawn. The Pandemic and Gender Inequality in Academia (July 20, 2020). https://ssrn.com/abstract=3666587

Lyttelton, Thomas, Emma Zang and Kelly Musick. 2020. “Gender Differences in Telecommuting and Implications for Inequality at Home and Work.” Available at SSRN 3645561.

Myers et al. 2020. “Unequal effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on scientists.” Nature Human Behaviour. pp. 1–4.

Oxfam, Promundo-US, & MenCare. 2020. “Caring Under COVID-19: How the Pandemic Is– and Is Not – Changing Unpaid Care and Domestic Work Responsibilities in the United States.” Technical report.

“Women in the Workplace 2020.” LeanIn.Org and McKinsey & Company. Technical report.